Hey – happy Sunday! This is part 2 of my series on the obesity epidemic in the United States and other developed nations. For an introduction to the topic at hand, click here.

The data for this week’s graphs were sourced from the CDC BRFSS, the USDA and the World Bank.

What causes obesity at the individual level? The answer is quite simple – a positive energy balance. What does that mean? To put on weight, whether it be lean tissue (muscle) or adipose tissue (fat), a person must metabolize more calories than they burn. This relationship can be seen visually in the graph below. On this graph, the X-Axis shows the average number of calories consumed at the population level for the United States, and the Y-Axis shows the % of American adults with obesity. The blue dots represent individual observations in this dataset, and the blue line shows the predicted relationship between the individual observations. See below:

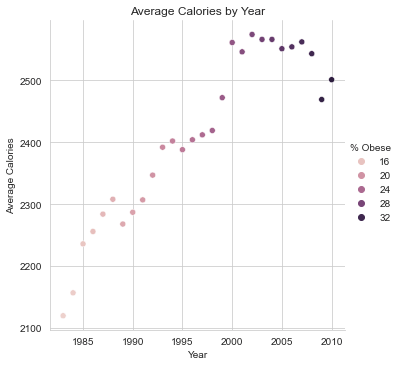

The next graph shows why obesity has increased at the most basic level: we are eating more. Here, the X-Axis is time, with years ranging from 1983-2010, and the Y-Axis shows the population-level average calories consumed daily. The color of the dots shows the % of American adults with obesity in the given year. See below:

At the most basic level, the answer to why we are collectively caring more weight as a nation is that we are eating more, but this answer isn’t actually very helpful in addressing the crisis we are facing. A more nuanced – and more useful – answer will tell us what specific factors are causing us to eat more and point us to solutions for population-level weight loss.

The first part of my useful answer will come from last week’s newsletter – obesity is the natural human reaction to our built food environment. To summarize, food is pleasurable, pleasurability increases for high-fat and high-carb foods, and high-fat and high-carb foods are readily available, cheap, and convenient due to our industrialized food production system. So, the first part of our nuanced answer for what causes obesity is the ubiquity of industrialized, mass-produced, highly-processed, extremely pleasurable foods.

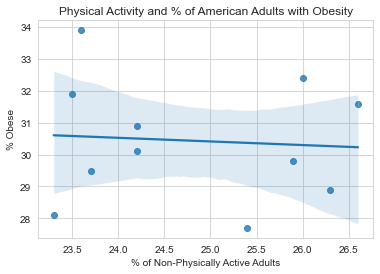

The second part of our answer comes from lack of exercise. At first glance, the data show that there isn’t a strong relationship between exercise and obesity. This graph shows that, over time, the % of American adults who do not report engaging in recreational physical activity (essentially, working out or exercising for the explicit purpose of getting exercise) and the % of American adults with obesity do not seem to correlate. See below:

But this graph doesn’t represent the whole picture. Intentionally working out actually makes up the minority of the movement most people get in a day. NEAT, or Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis, is the scientific term for calories burned doing everyday tasks; think walking up the stairs at work, going grocery shopping, doing the dishes, or cooking dinner. Studies show that NEAT is responsible for anywhere from 15-50% of the calories an average person burns in a day.

As it happens, NEAT for the average American is down quite a bit. NPR has reported that Americans are spending less time in nature than in the past, working from home is more common than ever, and potentially most obviously, our ever-rising screen time numbers represent hours of the day in which we are sedentary. Americans aren’t necessarily exercising less, but we are most certainly moving less, and that lower NEAT is likely a large part of the climbing rates of obesity.

The third cause for the increase in obesity rates, especially the spike we saw during the pandemic, is likely increased stress and the toll it is taking on our collective mental health. Think about the last three years – COVID, Black Lives Matter, the 2020 election, the war in Ukraine, inflation, countless mass shootings – all of these events put increased stress on our national consciousness and took a toll on our already precarious mental health. How does this relate to obesity? Studies consistently show that stress releases cortisol, and cortisol stimulates appitite. Stress is strongly correlated with weight gain, as anyone who stress-eats will tell you.

To conclude, Americans are eating more than ever, likely due to the incredibly convenience of industrially manufactured, calorie-dense foods; Americans are getting less NEAT because of lifestyle changes in increased screen time post pandemic; and Americans are reporting sky-high levels of stress which can lead to unintentional weight gain. We now have three potential approaches to address the obesity epidemic with public policy, but unfortunately it’s not that straight forward. Next week, I will show how obesity is a class issue, and how any attempt to address obesity with public policy must also address racial and economic inequity.

Thanks for reading, have a great week, and I’ll see you next Sunday. Don’t forget to subscribe.

Leave a reply to The Obesity Epidemic Part 4: Incretin Mimetics and the End of Obesity – Data Driven Politics Cancel reply