Hey – happy Sunday! This week is the start of a 4-part series on the obesity epidemic in the United States. Part 1 (today) will function as an introduction to the topic and an explanation of why I believe our metabolic health crisis cannot be solved at the individual level; part 2 will delve into the population-level causes for the obesity crisis; part 3 will cover the racial, economic, and social inequities found in the data on obesity; finally, part 4 will address my preferred public policy interventions for addressing the crisis.

The data for this week were sourced from the CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

I know metabolic health doesn’t seem particularly germane to a blog titled “Data Driven Politics,” but I disagree. Why? Obesity is a public health crisis. I firmly believe that obesity cannot be solved at the individual level and therefore must be addressed with public policy – a topic well within my wheelhouse.

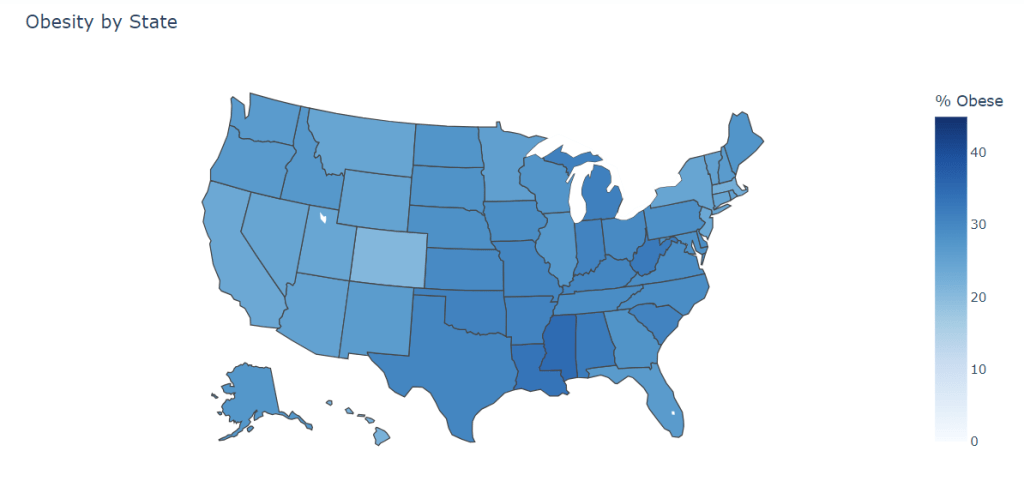

This week, I have a map of obesity by state in 2020. For an animated, interactive map showing change in obesity by state from 2011 – 2021, click here. To watch the animation on the hyperlinked map, click the “play” button in the bottom-left corner. To interact with the hyperlinked map, select a specific year with the slider below and scroll your mouse over (or tap your finger on) each state. See the non-interactive version below:

As can clearly be seen, the United States – like almost all other WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Developed) nations – has a problem. We are pushing an obesity rate of 36% and growing. The interactive version of the above graph (click here to see that) shows how precipitously the obesity rate has climbed in the past decade. While it is clear that obesity is a crisis numerically, this topic deserves more nuance than a graph of percentages.

Before going any further, I want to address the controversy inherent to writing about weight. First, I am all for the fat acceptance movement. This movement has been highly successful at reducing the stigma around being fat (the preferred term by the movement, as I understand it, and the one I will be primarily using going forward). Within my relatively short lifetime, I have seen beauty standards rapidly shift and fat bodies become far more visible in popular culture. With that said, I do not accept the contention that excessive adiposity (the scientific term for the energy, or “fat” stored by adipocytes, or “fat cells”) is in any way benign. Obese people – defined by a BMI (body mass index) of 35 or higher – have an increased risk of heart disease, diabetes, stroke, cancer, and all cause mortality in general. There is also scientific evidence that high BMIs are significantly associated with internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety. Obesity is not good for your health.

Even with all of the above statements generally being accepted as true by the scientific community, there are still many questions about the degree to which obesity is bad for your health, how long you have to be obese before your all cause mortality increases substantially, how the effect obesity has on mental health is likely bidirectional and multicollinear (put in simple terms, does obesity make you depressed or does depression cause you to gain weight?), how the stigma around fatness is measurably harmful, to what degree are fat people treated worse by the healthcare system, and to what extent genetics influence metabolic efficiency and adipocyte deposition (or how your genes impact how much fat you store), among many, many others.

Needless to say, this topic is incredibly multifaceted, and I will not be able to cover all aspects of it in this series. What I will cover is how obesity and public health interact with social and economic policy.

My last note before I let you go this week is to reiterate that obesity is a public health issue that cannot be solved at the individual level. If it could, close to 40% of the United States would not be obese. With how aware we all are of the harms of fatness on our health, no one would willingly be obese for their lifetimes. While it cannot be reasonably said that no single fat person got to their body composition through poor decision making, it is intellectually dishonest and materially harmful to assume that all fat people are gluttons with no regard for their health.

Humans evolved in a pre-historic world where food was scarce and the best thing to do for survival was to consume as many calories (specifically carbs and fat) as physically possible when they happened to be available. Our medullas (“primitive brains”) evolved even further back in time when mammals were gatherers as much as they were hunters. Animal brains are fundamentally programmed to consume as many calories as they can at all times and to consider stored fat as a survival buffer.

In our modern world, we have intensely rich and calorie-dense food available to be delivered from restaurants and grocery stores at the click of a button. Soda, candy, chips, baked goods, and many other favorite foods of modern people are specifically designed to be as pleasurable as possible when we eat them. The dopaminergic effects (pleasure from dopamine) of calorie dense food on our “primitive brain” are well documented and to powerful for our more recent frontal cortex to overcome.

For an example of how incredibly challenging it is to eat healthy in the modern world, just look at the nutrition information for the salads at your favorite restaurant – I would bet many of the salads with dressing are as energy-dense as a cheeseburger.

Obesity is the natural mammalian reaction to the modern food system we have built. We can either rebuild the food system – an incredibly costly and unlikely solution to our problems – or we can implement sensible public health measures to address this epidemic. I hope you join me for the next three weeks as we examine the inequalities in our obesity epidemic, go deeper into the data behind the causes of our epidemic, and lastly, address the common-sense public health solutions to obesity.

Thanks for reading, happy Fourth of July, don’t forget to subscribe, and I’ll see you next week.

Leave a reply to The Obesity Epidemic Part 4: Incretin Mimetics and the End of Obesity – Data Driven Politics Cancel reply