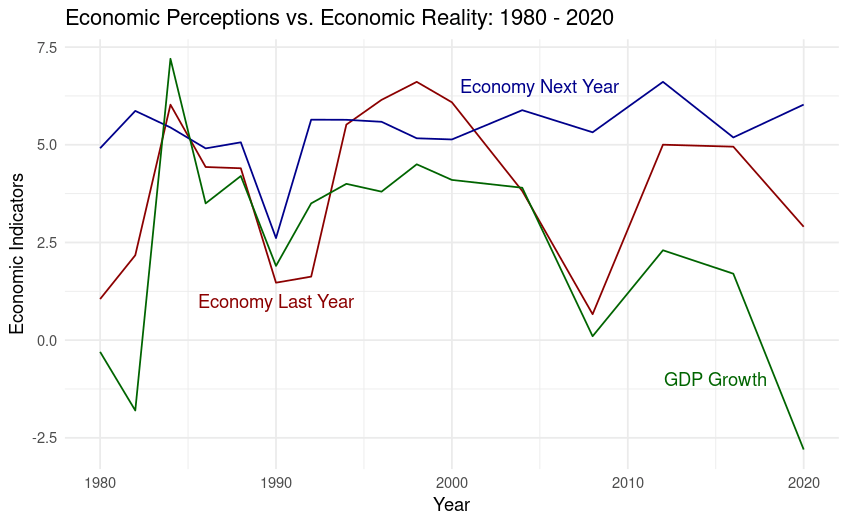

I do not think it is controversial to say most people are pretty bad at predicting the future – economists included. But how bad are they really? This graph I made using data from the ANES might give us a clue:

On this graph, the red line represents how Americans think the economy was the previous year on a 1-3 scale (adjusted here to a 0-5-10 scale to fit with GDP %), the blue line represents how Americans think the economy will be the coming year (same scale and adjustment as the red line), and the green line represents actual GDP growth.

As can be seen here, since the 1980s, we are *reasonably* good at appraising how strong the economy was the previous year, but we are significantly more optimistic about the future than what is reasonable. It also appears that we have gotten worse at forecasting the economy since the turn of the 21st century.

How does this finding impact politics? First, real economic conditions effect turnout. According to Rosenstone (1982) and Southwell (1988), economic surpluses lead to higher voter turnout, and economic recessions lead to lower voter turnout. This hypothesis is rather intuitive – when people have limited resources, they are inclined to focus on resource-generating activities (like working more or starting gig-work); conversely, when people have surplus resources, they are much more likely to engage in resource-expending (like going on vacation) or resource-neutral activities (like voting). Scholars call this the “withdrawal hypothesis.” This hypothesis is also the best explaination I’ve seen to explain the discrepancies in voter turnout between the rich and the poor on an individual level.

Economic perceptions also directly effect the choices people make when they actually turn out to the ballot box. Lewis-Beck and Martini find that the percentage chance of the average voter choosing to cast a vote for the incumbent president goes down by nearly 60%. This is a correlation coefficient not often seen in the social sciences, and shows just how impactful economic perceptions are on presidential elections.

Economic perceptions obviously matter in presidential vote choice, and Wlezen et al. find that retrospective economic appraisals influence vote choice far more than prospective appraisals. This finding matches very well with the red line on my graph during presidential election years.

So what explains the massive gap between prediction and appraisal measures and actual economic performance? I believe a substantial portion of the discrepancies seen in the above graph can be attributed to “recency bias,” or how the magnitude of our recent experiences can alter our perspective of the relative magnitude of future events. When our baseline was the strong economy of the 1990s, our optimism was more reasonable; when our baseline became the post-2008 economy, all of the sudden small GDP growth became something to get excited about.

Awareness of our cognitive biases is a great skill for both working in the social sciences and for life more broadly. If you catch yourself underestimating or overestimating the significance/magnitude of an event in your life simply based on its significance/magnitude relative to recent events, you can pause, thank me, subscribe to my blog, and proceed with more caution in the future.

Thanks for reading and I’ll see you next weekend.

Leave a reply to Serena Cancel reply